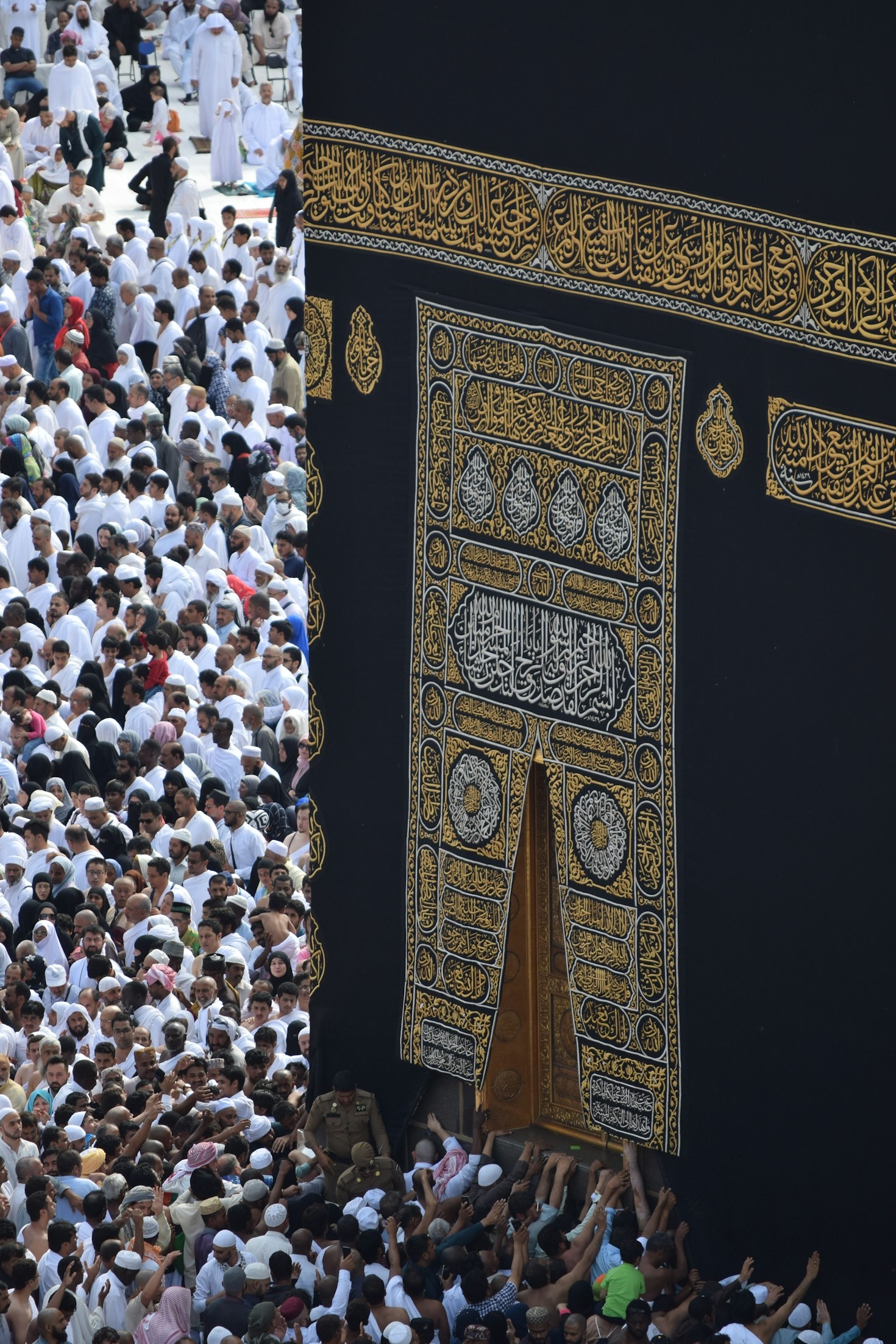

The Kaaba, situated at the center of the Holy Mosque in Mecca, represents the most revered site in Islam. As the central point of Muslim devotion, the Kaaba carries immense significance for Muslims globally. This article delves into the historical, spiritual, and architectural relevance of the Kaaba, elucidating why it is venerated by over a billion Muslims. Through this detailed guide, you will acquire a more profound insight into the Kaaba’s significance within Islamic faith and tradition.

What is the Ka’aba?

The Ka’aba, meaning “cube,” is the most hallowed site in Islam, referred to as the sacred bayt Allah (House of God). It is positioned at the core of the sacred mosque Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Who constructed the Ka’aba?

Under the command of Allah (SWT), Prophet Ibrahim (AS) was the first to construct the Ka’aba:

“And remember Ibrahim and Ismail raised the foundations of the House (With this prayer): “Our Lord! Accept (this service) from us: For Thou art the All-Hearing, the All-knowing.”

Quran, 2:127

History of the Ka’aba

In the initial period of Islam, Muslims prayed towards Jerusalem. Currently, we direct our prayers towards Makkah, following the Qur’anic revelation that instructed this change in direction.

Now, turn your face in the direction of the Sacred Mosque (Al-Masjid-ul-Harām), and (O Muslims), wherever you are, turn your faces in its direction.”

The Origin of the Kaaba: Constructed by Prophet Ibrahim and Ismail

The narrative of Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) and his son Ismail (Ishmael) is deeply intertwined with the origin of the Kaaba. According to Islamic tradition, Allah instructed Prophet Ibrahim to erect the Kaaba as a sanctuary for the worship of the One God. The Quran narrates how Ibrahim and Ismail elevated the foundations of the Kaaba while seeking Allah’s blessings. This event signified the commencement of the Kaaba’s role as the spiritual nucleus of monotheism.

The inhabitants surrounding the Kaaba during this period included Ismail and the Jurhum tribe, who originally hailed from Yemen. The architects crafted the Kaaba in a nearly square form, with its sides deliberately oriented towards the cardinal directions. This configuration not only represented the universality of Islam but also guaranteed that the structure would withstand strong winds without sustaining damage. The construction by Ibrahim and Ismail remained intact for many years, upholding its sanctity as a place of worship.

The Initial Rebuilds: Al-Amaliqah and the Jurhum Tribe

The al-Amaliqah tribe was the first to reconstruct the Kaaba, followed by the Jurhum tribe, or perhaps in the opposite sequence. These early reconstructions ensured that the Kaaba continued to be a significant and venerated edifice in the area. Each rebuilding preserved the original design and intent of the Kaaba, maintaining its importance as a site of worship dedicated to the One God.

The Kaaba Under Qusayy Ibn Kilab: Solid Foundations and Council House

Centuries later, Qusayy Ibn Kilab, an ancestor of the Prophet Muhammad (SAW), assumed responsibility for the management of the Kaaba. This event took place in the second century prior to the Hijrah (migration). Qusayy dismantled and reconstructed the Kaaba on more robust foundations, ensuring its longevity. He also added a roof constructed from doom palm timber and date-palm trunks, which further fortified the structure’s resilience.

Qusayy’s contributions extended beyond the Kaaba itself. He also established ‘Daru ‘n-Nadwah,’ the Council House, adjacent to the Kaaba. This council house became the focal point of Qusayy’s governance, where he convened with his advisors and made significant decisions. Furthermore, Qusayy allocated different sides of the Kaaba to various clans of the Quraysh tribe. Each clan constructed their residences on the side assigned to them, with entrances facing the Kaaba, symbolizing their connection to this holy site.

The Great Flood and the Reconstruction by the Quraysh

Five years prior to the moment when Prophet Muhammad (SAW) received his initial revelation, a catastrophic flood inundated Mecca, causing extensive damage to the Kaaba. The Quraysh tribe, which held the responsibility for the maintenance of the Kaaba, resolved to undertake its reconstruction. They allocated various tasks related to the rebuilding process among themselves, showcasing their unified commitment to safeguarding the Kaaba.

In order to guarantee the quality of the reconstruction, the Quraysh engaged a builder from Rome and a carpenter from Egypt. Their expertise played a crucial role in the reconstruction of the Kaaba using the finest materials accessible. Nevertheless, the endeavor was fraught with difficulties. When the moment arrived to reinstall the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad), a contention emerged among the Quraysh clans regarding who would be honored with the task of placing it. The prudent intervention of Prophet Muhammad (SAW), who was then thirty-five years old, settled the disagreement. He proposed that the stone be placed on a robe, with each clan grasping a corner of it. Collectively, they elevated the stone, and the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) positioned it correctly, thereby averting conflict and solidifying his reputation for wisdom and impartiality.

Despite their diligent efforts, the Quraysh discovered that their financial resources were depleted before they could restore the Kaaba to its original dimensions. Consequently, they opted to reduce the size on one side, omitting a section of the original foundation. Today, this excluded area is recognized as ‘Hijr Ismail’ (the Enclosure of Ismail), which continues to hold significant historical and structural importance within the context of the Kaaba.

The Kaaba During the Siege of Makkah and the Rule of Abdullah Ibn Az-Zubair

The history of the Kaaba experienced a significant shift during the governance of Yazid Ibn Muawiyah, particularly when Abdullah Ibn Az-Zubair asserted his authority over Hijaz. A siege orchestrated by Husain Ibn Numair resulted in catapults targeting the Kaaba, inflicting considerable damage. The Kiswah, which is the covering of the Kaaba, along with several roof timbers, was set ablaze, leaving the structure in a state of disrepair.

Following the conclusion of the siege, news of Yazid’s demise reached Makkah. Abdullah Ibn Az-Zubair, with a resolute intention to restore the Kaaba to its foundational integrity, resolved to demolish and reconstruct it. He sourced high-quality mortar from Yemen and erected a new edifice that re-incorporated Hijr Ismail within the Kaaba’s perimeters. Additionally, he implemented two doors—one designated for entry and the other for exit—to enhance the movement of pilgrims. The builders elevated the Kaaba to a height of twenty-seven arms, perfumed the entire structure, and adorned it with a silken Kiswah. This reconstruction was finalized on the 17th of Rajab, 64 A.H., signifying a pivotal moment in the Kaaba’s historical narrative.

The Kaaba Under Abdul-Malik Ibn Marwan and Hajjaj Ibn Yusuf

The structure of the Kaaba underwent modifications once more when Abdul-Malik Ibn Marwan assumed power in Damascus. Following his victory over Abdullah Ibn Az-Zubair, his commander Hajjaj Ibn Yusuf examined the Kaaba and observed the alterations made by Ibn Az-Zubair. Abdul-Malik commanded that the Kaaba be restored to its original form as designed by the Quraysh. Hajjaj dismantled six and a half arms from the northern side, elevated the eastern door, and sealed the western one, effectively reverting the Kaaba to its condition prior to Ibn Az-Zubair’s changes.

Ottoman Contributions and the Great Flood

The Ottoman Sultans significantly contributed to the upkeep and restoration of the Kaaba. Sultan Sulaiman, who began his reign in 960 A.H., modified the roof of the Kaaba, thereby ensuring its ongoing protection against the elements. Subsequently, Sultan Ahmad, who ascended the throne in 1021 A.H., implemented additional repairs and modifications to the structure.

Nevertheless, the Kaaba encountered yet another obstacle with the great flood of 1039 A.H. This flood inflicted damage on sections of the Kaaba’s northern, eastern, and western walls, leading Ottoman Sultan Murad IV to mandate extensive repairs. These restorations guaranteed that the Kaaba remained intact and continued to function as the central point of Islamic worship. The edifice, as reconstructed under Sultan Murad IV, has largely retained its form to the present day.

The Shape and Structure of the Kabah The Kabah is a nearly square edifice constructed from hard, dark bluish-grey stones, which reflect its ancient and durable design. Presently, the Kabah stands at a height of sixteen meters, although it was considerably shorter during the era of the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him). This is illustrated by the account of the Prophet lifting Ali Ibn Abu Talib onto his shoulders to remove and destroy the idols situated on the roof of the Kabah during the conquest of Makkah.

The dimensions of the Kabah are meticulously defined and hold profound significance. The northern wall, which faces the Enclosure of Ismail (Hijr Ismail) and incorporates the Trough of Mercy (Mizab al-Rahmah), along with the corresponding southern wall, each measures ten meters and ten centimeters in length. The eastern wall, which contains the entrance, and the opposite western wall extend to twelve meters in length. The entrance of the Kabah is positioned two meters above the ground, necessitating the use of a staircase for access.

A crucial element of the Ka`bah is the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad), which is set into the east-south corner. It is situated one and a half meters above the circumambulation area (Mataf), welcoming those who enter through the door on their left. The Black Stone, characterized by its irregular oval form and a diameter of approximately thirty centimeters, exhibits a black hue with a reddish tint. Over time, red dots and yellow wavy lines have emerged on the Stone as a result of the soldering and joining of its fractured pieces.

The Corners of the Kabah The corners of the Kabah are held in high esteem, each designated with a specific name: the northern corner is referred to as the Iraqi Rukn, the western corner as the Syrian Rukn, the southern corner as the Yemenite Rukn, and the eastern corner, which houses the Black Stone, is known as the Black Rukn. Pilgrims identify the area between the entrance and the Black Stone as Al-Multazam, a revered location where they embrace the wall in prayer and supplication.

Atop the northern wall rests the Trough of Mercy (Mizab al-Rahmah), a feature introduced by Al-Hajjaj Ibn Yusuf. This trough has undergone replacements over the years by various rulers, with the current iteration crafted from gold, installed by Sultan `Abdul-Majid in 1273 A.H.

Opposite the northern wall lies Al-Hatim, a semi-circular structure that resembles a bow, with its ends oriented towards the Iraqi and Syrian Rukns. The distance between the extremities of Al-Hatim and these Rukns is measured at two meters and three centimeters. Al-Hatim has a height of one meter and a width of one and a half meters, and it is adorned with intricately carved marble panels. The area situated between Al-Hatim and the northern wall, referred to as Hijr Ismail, encompasses approximately three meters that were originally part of the Kaabah constructed by Prophet Ibrahim (peace and blessings be upon him).

The Covering of the Ka`bah

The Kaabah, regarded as the most sacred site in Islam, has been draped with a covering known as the Kiswah since ancient times. The practice of covering the Kaabah commenced with the Tubba’ kings of Yemen, beginning with Tubba Abu Bakr As’ad. His successors perpetuated this tradition, adorning the Kaabah with various types of sheets, often layering them atop one another. As the coverings aged, they were replaced with new ones, a custom that persisted until the time of Qusayy Ibn Kilab.

Qusayy, a forebear of the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him), formalized the practice by instituting a tax on the Arabs to ensure that a new covering was placed on the Kaabah each year. This system was maintained by his descendants. Abu Rabiah Ibn Al-Mughirah was responsible for arranging the Kaabah’s covering every other year, alternating with the clans of Quraysh.

During the era of the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him), the Kaabah was draped with sheets from Yemen, a tradition that persisted beyond his lifetime. When the Abbasid caliph Al-Mahdi made a pilgrimage to the Kaabah, the attendants of the House expressed their worries regarding the excessive weight of the coverings on the roof, fearing a potential collapse. In response to their concerns, Al-Mahdi ordered the removal of all old coverings and instituted a new practice: replacing the old covering with a new one each year. This tradition remains in effect to this day.

The mother of Abbas initiated the practice of draping the Kaabah from the inside to fulfill a vow associated with her son.

Islamic studies continue to explore these historical practices and their significance.

Modifications to the Ka`bah

Early Expansions and Renovations: The second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab (ruled 634–644), enlarged the vicinity of the Kabah to accommodate a greater number of pilgrims. His successor,Uthman ibn Affan (ruled 644–656), constructed colonnades surrounding the open plaza and integrated significant monuments into the sanctuary.

During the civil conflict between Caliph Abd al-Malik and Ibn Zubayr in 683 CE, the Kabah was engulfed in flames. Accounts suggest that the Black Stone fractured into three segments, which Ibn Zubayr subsequently reassembled using silver. Ibn Zubayr reconstructed the Kabah with wood and stone, adhering to the dimensions established by Prophet Ibrahim (peace and blessings be upon him) and paved the surrounding area. Following Abd al-Malik’s reclamation of Mecca, he restored the structure to its original design.

During the Umayyad era, under Caliph al-Walid (ruled 705–715), the mosque encircling the Kabah was adorned with mosaics, akin to those found in the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus. By the seventh century, the Kabah was draped in kiswa, a black cloth that is replaced annually during the Hajj. The Abbasid period (750–1250) witnessed numerous expansions and alterations to the mosque surrounding the Kabah. Travel writers such as Ibn Jubayr, who visited in 1183, noted that the Kabah maintained its Abbasid structure for several centuries.

Mamluk and Ottoman Renovations: Between 1269 and 1517, the Mamluks of Egypt governed the Hijaz region, home to Mecca. Sultan Qaitbay, who ruled from 1468 to 1496, established a madrasa (religious school) next to the mosque. The Ottoman sultans, Süleyman I (reigned 1520–1566) and Selim II (reigned 1566–1574), undertook extensive renovations of the complex. Following devastating floods in 1631 that destroyed the Kabah and the adjacent mosque, a thorough reconstruction was executed. The mosque that stands today boasts a vast open area with colonnades on all four sides and seven minarets, the highest number found in any mosque worldwide. The present structure features the Kabah at its core, encircled by numerous other sacred buildings and monuments.

The Black Stone

The Black Stone, known as Hajar al-Aswad, is one of the most revered objects in Islam, situated in the eastern corner of the Kaaba. This sacred stone carries immense significance for Muslims around the globe and is a vital component of the Hajj pilgrimage. Below is an in-depth exploration of its importance, historical context, and its role in Islamic worship.

Description and Appearance

The Black Stone is positioned in the southeastern corner of the Ka`bah within Masjid al-Haram, the holiest mosque in Islam. It possesses an irregular oval shape, with a diameter of approximately 30 centimeters. The surface of the Black Stone is predominantly black, interspersed with reddish tones, red speckles, and yellow lines resulting from repairs and exposure. Elevated about 1.5 meters above the Mataf, it is a prominent feature that pilgrims strive to touch or kiss.

Historical and Religious Significance

Origin: According to Islamic tradition, Allah sent the Black Stone from Heaven to the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) and his son Isma`il (Ishmael) as a divine sign. Initially, it was white, but it turned black over time due to the accumulation of human sins. This change symbolizes the burden of human transgressions and the aspiration for redemption.

Role in Pilgrimage: The Black Stone is integral to the rituals of Hajj and Umrah, the Islamic pilgrimages to Mecca. During the Tawaf, pilgrims circumambulate the Ka`bah seven times, with the Black Stone serving as a focal point of this ritual. Pilgrims seek to touch or kiss the Black Stone as an expression of respect and to invoke Allah’s blessings. This act of reverence is deeply embedded in the Sunnah, the practices and traditions of the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him).

Symbolism: The Black Stone embodies the unity of the Muslim Ummah (community) and acts as a tangible connection between the earthly realm and the divine. It is viewed as a vessel for prayers and supplications, absorbing the spiritual aspirations of those who approach it. Its presence at the Ka`bah highlights the bond between the faithful and their Creator.

Historical Events and Repairs

Throughout the annals of history, the Black Stone has encountered numerous adversities. During the civil conflict between the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik and Ibn Zubayr, both the Kaaba and its Black Stone suffered damage. In the year 683 C.E., the Black Stone fractured into multiple fragments. Ibn Zubayr rejoined the pieces using silver, and subsequently, Abd al-Malik restored the sections of the Kaaba that had been originally designed by the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him).

Despite these challenges, the Black Stone endures as a symbol of resilience and faith. It has been meticulously preserved and continues to occupy a pivotal role in the spiritual lives of Muslims.

The Black Stone in Islamic Tradition

Numerous hadiths (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) underscore the significance of the Black Stone. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) kissed the Black Stone and encouraged Muslims to regard it as sacred.

Spiritual Connection: For Muslims, the Black Stone signifies a tangible connection to the divine. Touching or kissing the stone is believed to confer blessings, forgiveness, and a profound sense of closeness to Allah. The rituals associated with the Black Stone are infused with deep spiritual meaning, reflecting the rich traditions of Islamic worship.

Prayer and Pilgrimage

Prayer: In Islam, prayer constitutes a fundamental act of worship. Muslims are obligated to pray five times daily. Following 624 CE, they established the direction of these prayers (qibla) towards Mecca and the Kaaba rather than Jerusalem. This alteration, as dictated by the Qur’an, ensures that Muslims globally face the Kaaba during their prayers.

Pilgrimage: One of the Five Pillars of Islam, it is obligatory for Muslims who are physically and financially able to undertake it at least once in their lifetime. Pilgrims convene in the courtyard of the Masjid al-Haram, encircling the Kaaba. They perform Tawaf, walking seven times around the Kaaba in a counterclockwise direction, with the intention of kissing or touching the Black Stone. This ritual is a vital aspect of the Hajj pilgrimage and symbolizes unity, devotion, and submission to Allah.

BAITULLAH – THE HOUSE OF GOD – BAITULLAH.COM